Mechanical switches are electrically noisy. What the firmware of your keyboard sees when a key is pressed is not a single clean 0 -> 1 transition, but a rattling sequence of 0’s and 1’s, which eventually stabilizes. To turn this flickering signal into a reliable pressed / released event, a firmware typically inserts a debouncing routine.

In this post, I want to dissect Peter Dannegger’s debouncing routine: a tiny, bit-parallel algorithm. Even if you don’t plan writing a keyboard firmware yourself in the next days, take a look at this algorithm: it’s quite elegant.

When you press or release a mechanical switch (Cherry MX, Alps, Kailh, etc.), the metal contacts do not transition cleanly from open to closed or vice versa. This “bounce” happens in both directions (press and release) and can last anywhere between 1-10 ms depending on switch geometry, spring tension, lubrication, and force.

A microcontroller scanning the key matrix might observe:

Time (ms): 0 1 2 3 4 5 6

Raw signal: 0 1 0 1 0 1 1

If the firmware reacted to every raw transition, this would generate multiple press/release events for a single physical key press/release.

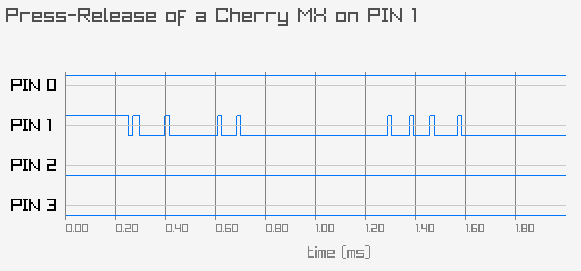

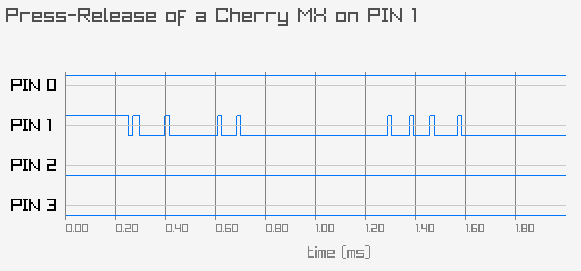

If you are like me and prefer seeing over simply believing, here is a simple measurement performed with the microcontroller in my keyboard for a single key press.

It does not show the real bouncing curve of the switch (that would require using an oscilloscope), but rather what the firmware would see for a single keypress. Note: the lines are initially high and a key press grounds the wire, so the transition is rather from 1 to 0 when pressing.

As I’ve mentioned in a previous post, I am slowly rewriting my keyboard firmware. My current debouncer is a hacky solution using a delay. In the search for a better solution, I’ve found this gem.

When we read a different value on the wire, we don’t immediately change our mind about the switch state, but rather record this information. Only after consecutively reading that new value for N times, we flip the state bit.

So we keep one bit for the stable state plus a counter of log(N) bits to track the number of consecutive diverging reads. Given the relatively low frequency of microcontrollers, every read is typically performed ~2ms apart and 4 reads should be sufficient to determine whether the signal is stable. Hence, a 2-bit counter suffices.

This simple debouncing routine would be like this:

val = READ_PIN();

if (state == val) {

count = 0;

} else {

count++;

if (count == N) {

count = 0

state = ~state

}

}

We never really write the read value into the state. We just flip the state bit when enough difference was observed – remember, val and state are 1-bit variables.

When we want to keep track of every key on a keyboard, we simply use an array of (state, counter) pairs with 30-100 such pairs depending on how spartan your keyboard is.

Although memory space in microcontrollers is limited, tracking the debouncing state of 100 keys is not a problem in practice. Still, for the sake of explanation, let’s assume we want to pack counters together to reduce RAM usage a bit.

Our counters only need 2 bits. For 8 keys, we would store one state byte and two counter bytes:

state = s0 s1 s2 s3 s4 s5 s6 s7

count0 = c00 c01 c10 c11 c20 c21 c30 c31

count1 = c40 c41 c50 c51 c60 c61 c70 c71

Here, sK is the state bit of key K and cK0 and cK1 are its counter bits.

Now imagine the hassle of working with these merged 2-bit counters, incrementing them, resetting individual counters, checking for overflow, and deciding when to flip the state.

Here enters Dannegger’s trick: We transpose the counters like this

ct0 = c00 c10 c20 c30 c40 c50 c60 c70

ct1 = c01 c11 c21 c31 c41 c51 c61 c71

With this configuration, we perform a kind of bit-parallel vectorization on a microcontroller! The complete algorithm for debouncing 8 keys in parallel boils down to this:

raw = READ_PINS();

i = state ^ raw;

ct0 = ~(ct0 & i);

ct1 = ct0 ^ (ct1 & i);

changed = i & ct0 & ct1;

state ^= changed;

Here the inputs are:

raw: the current scan of the pin matrixstate, ct0, ct1: the internal debouncer stateand the outputs are:

statechanged indicating which keys flippedEach key is represented by three bits inside the machine words:

state[k]: the stable debounced value of key kct0[k], ct1[k]: a 2-bit ladder (a 4-step down-counter)The bits in the variable i mark which keys currently disagree with the stable state (state ^ raw). These are the keys for which the ladder should advance.

The updates to ct0 and ct1 encode the ladder transition: For keys that disagree (i = 1), the ladder steps through 11 → 10 → 01 → 00 → (overflow) → 11, and when the overflow happens, changed is asserted. Any agreement (i = 0) immediately resets the ladder back to 11.

Here are the steps showing a transition from 0 to 1 (the opposite transition works symmetrically):

| raw | state | i | (ct1 ct0) | comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 1 | stable, ladder held at 11 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 0 | 1st disagreement |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 1 | 2nd disagreement |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 0 | 3rd disagreement |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 1 | 4th disagreement -> flip state |

This is done bitwise: if the variables are 8-bit, we can support 8 keys; if they are 32-bit, the same code works for 32 keys. If you wanted 8 or 16 consecutive samples instead of only 4, you’d need 3 or 4 ladder bits, and the transpose trick generalizes in the obvious way (more ct words). Pretty neat, isn’t it?

Dannegger’s debouncer works like a bit-level SIMD: each bit position represents one key, and each instruction operates on all keys at once.

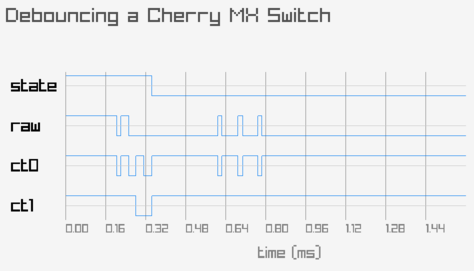

My low-level skills are rusty, and all this bit-twiddling makes me unsure about correctness. Again, better seeing than believing:

This figure shows the debouncer in action. The raw line is the direct output of the pin; state, ct0, and ct1 are the values of the debouncer variables. The readings are performed in a tight loop without sleeps, so this is the fastest frequency I could read from the pin. One can see that the ct0 is set, but is immediately reset whenever the raw line bounces. After that, there is now enough confidence of the state change and the pair ct1 ct0 go from 11 to 00, flipping the state bit.

This is reassuring, but if we care about correctness we need a specification. The best specification I could come up with was these two properties:

The two properties above fully describe the user-visible behavior of a correct debouncer and can be used to create a strong set of test cases for a real implementation, tracking all keys. I’ll report about that next time.

More references:

Although it is complete overkill, the two properties above naturally call for a more formal treatment of this algorithm. I’m going to use TLA+ and I already apologize for the digression.

We start with the model variables: raw is the environment input, debouncer is a record with the implementation state, and ghost is a specification variable used to precisely define the properties later on.

---- MODULE Dannegger ----

EXTENDS Naturals, TLC, Sequences

VARIABLES

raw, \* environment input

debouncer, \* record for implementation (ct0, ct1, state)

ghost \* ghost queue and state for verification

vars == << raw, debouncer, ghost >>

Init ==

/\ raw \in BOOLEAN

/\ \E state \in BOOLEAN:

/\ debouncer = [ state |-> state, ct0 |-> TRUE, ct1 |-> TRUE ]

/\ ghost = [ queue |-> <<>>, prev |-> state ]

Init picks an arbitrary value for raw and for the current state. The ladder starts reset with both bits set to TRUE. The ghost variable contains an empty queue and the previous state. The queue tracks the last raw values provided by the environment. The prev state will be used to identify when the debouncer’s state flips.

The debouncer algorithm is pretty much a translation of the C code from before:

\* Implementation step: Dannegger's Debouncer

NextImpl ==

LET

i == debouncer.state # raw

ct0 == ~ (debouncer.ct0 /\ i)

ct1 == (ct0 # (debouncer.ct1 /\ i))

changed == i /\ ct0 /\ ct1

state == debouncer.state # changed

IN

/\ debouncer' =

[ debouncer EXCEPT

!.state = state,

!.ct0 = ct0,

!.ct1 = ct1

]

Since TLA+ does not have an infix XOR operator, I used the inequality # operator, which is equivalent here.

To keep this model simple, I decided encoding the next step of environment and ghost variable together.

NextEnv ==

/\ raw' \in BOOLEAN

/\ LET q == IF Len(ghost.queue) < 4

THEN Append(ghost.queue, raw)

ELSE Tail(ghost.queue) \o << raw >>

IN ghost' = [ queue |-> q, prev |-> debouncer.state ]

Here, we pick some arbitrary value for the next raw' value. We always append the current raw value to the queue, but when it already contains 4 items, we also drop the oldest item to maintain the queuelength constant.

The combined Next step and Spec definition follow the typical TLA+ pattern:

Next ==

/\ NextEnv

/\ NextImpl

Spec == Init /\ [][Next]_vars /\ WF_vars(Next)

The most interesting part is the invariants: TypeInv, Safety and Progress.

TypeInv ==

/\ raw \in BOOLEAN

/\ debouncer \in [

state : BOOLEAN,

ct0 : BOOLEAN,

ct1 : BOOLEAN

]

/\ ghost \in [

queue : Seq(BOOLEAN),

prev : BOOLEAN

]

/\ Len(ghost.queue) <= 4

Disag(q, v) ==

/\ Len(q) = 4

/\ \E b \in BOOLEAN :

/\ \A i \in 1..4 : q[i] = b

/\ b # v

Flipped ==

debouncer.state # ghost.prev

(* Flips only happen after four consecutive disagreements. *)

Safety ==

/\ Flipped => Len(ghost.queue) >= 4

/\ Flipped => Disag(ghost.queue, ghost.prev)

(* Four consecutive disagreements cause an immediate flip. *)

Progress == Disag(ghost.queue, ghost.prev) => Flipped

====

TypeInv follows the typical pattern. Safety encodes the first property from above: If a flip occurs, then the last four raw observations must all agree with each other and disagree with the previous state.

Progress is encoded as an invariant because, in this model, it is a stronger statement than mere eventuality. If the queue has 4 observations that disaggree with the previous state, then we must have flipped.

© 2025 db7 — licensed under CC BY 4.0.